Time passes differently in the third volume of the Wild Cards series, Jokers Wild. The first book spanned decades, from the end of WWII to the 1980s. In the second book, time jumped back and forward, here and there, before mostly settling in for a two year stint. In Jokers Wild, the passage of time slows evermore, caught on a single day, with each chapter marking off the hours.

It’s Wild Card Day, 1986. Forty years have passed since the alien virus was released by human villain Dr. Tod. New York City celebrates, commemorates, and manages to barely escape yet another disaster, thanks to the post-virus villain the Astronomer. In his eyes, it’s Judgement Day. He plans to spend it murdering all the aces who opposed him at the Cloisters, before jetting off into the galaxy on a stolen spaceship. He sends forth his minions Demise and Roulette to kill various aces, but both are desperate to escape him and will turn on him in the end. By then, a slew of aces are dead (or presumed dead), including the Howler, the Turtle, and Modular Man.

Hiram Worchester passes the day preparing for a Wild Card Day party at his upscale restaurant, Aces High—though he ends up flirting with the idea of fighting bad guys alongside detective Jay Ackroyd (Popinjay). Wraith, New York’s scantily-clad-Robin-Hood-librarian, gets into trouble after stealing a secret book from Kien, leader of the Shadow Fist Society. Kien’s archnemesis, bow-and-arrow vigilante Brennan, spends his time running after the bikini-clad thief, then aiding her as the duo attempt to trip up Kien and his lawyer, Loophole Latham.

Sewer Jack consumes most of the day searching for his niece Cordelia, while Bagabond assists, though she is ultimately forced to re-evaluate her relationship with Jack, Rosemary, and her own animals. Rosemary the do-gooder begins to think that doing good might require a little more ruthlessness, especially when it comes to controlling the Mafia.

Fortunato gathers up the Cloister’s aces in an effort to protect them from the Astronomer before engaging in a final showdown with him above the city. He (finally) defeats the guy, while the other villain, Kien, gets to keep ruling his gang, even if he does suffer an upset thanks to the now romantically-inclined Wraith and Brennan.

Unlike the previous novel, composed of discreet chapters by different authors, Jokers Wild is the first true mosaic novel in the Wild Cards series. Seven authors wrote their own sections, which the editor stitched together into one story. The main POVs this time around are Demise, Roulette, Wraith, Fortunato, Jack, Bagabond, and Hiram.

Several POV characters spend a great deal of the novel chasing Kien’s stolen books around the city or looking for Jack’s niece Cordelia. While the never-ending searches may not be the most scintillating of plot devices, they do link the various storylines and characters together, much as the singularity shifter (bowling ball) did in Wild Cards II. And much like with the bowling ball, halfway through the book I thought if I had to see Kien’s books one more time, I’d light the things on fire. Cordelia I just couldn’t care less about; I found her overwhelmingly TSTL.

Wild Cards in the City

The previous volume in the series, Aces High, drew especially heavily on the sci-fi and horror genres, with its plot extending outside of NYC to other parts of the US and eventually into space, but in Jokers Wild the alien aspect mostly disappears from the narrative. Instead, the book relentlessly focuses on NYC, with the action carefully mapped out across the street grid, the city’s neighborhoods, and its landmarks. More so than the previous two books, it’s decidedly urban, akin to the settings of Batman and Watchmen (with their gritty cityscapes Gotham and the alt-history NYC). New Yorkers and their city really come to the fore here, where baseball fans, anti-Jersey prejudice, and vermin-infested trash barges abound.

A great thing about this book is that it asks a question I didn’t know I needed answered: How does NYC commemorate Wild Cards Day? Well, pretty much as you’d expect. The bulk of the celebrations occur in Jokertown, including drunken block parties, fireworks, sno-cones, and even the Joker Moose Lodge Bagpipe Band. Parades clog the streets with homemade crepe paper floats depicting famous figures: “There was Dr. Tod’s blimp and Jetboy’s plane behind it, complete with floral speed lines.” Politicians give speeches and take advantage of photo ops. Celebrities attend ritzy parties; average joes call in sick. Tourists swarm the streets, but when the privileged nats finally leave, homeless jokers rule the night.

In this book we spend most of our time with aces, rather than jokers. (I wish the book titles had been switched, since WCII followed more jokers and WCIII emphasizes aces and the restaurant Aces High!) The holiday celebrations illuminate the divide between these two groups. The jokers carouse down in Jokertown, the streets open to all and filled with booths that benefit jokers and the needy. The aces, in contrast, gather together at the top of the Empire State Building, at the closed party thrown by Hiram in his swank restaurant. Invitations go out to the aces “who counted” and door staff only admit gate crashers if they can demonstrate an ace power. In other words, no jokers allowed. Hiram ignores Captain Trips’ criticism when the hippy laments, “I mean, it’s like elitist, man, this whole dinner, on a day like this it ought to be aces and jokers all getting together, like, for brotherhood.”

And Trips is correct. Yes, Hiram’s party is elitist. Yes, it’s classist. But it also exemplifies genetic discrimination. After all, the distinction that governs whether one can cross Hiram’s vaunted threshold is based on how one’s DNA responds to the Xenovirus Takis-A, and nothing more.

In so many ways I find Hiram to be an ambivalent character; don’t even get me started on his love of “innocent women.” In the past he’s dabbled in do-gooder-ness, but recognized that he didn’t have what it took to be a hero. Yet he spends the entire book flirting with the desire to save people, although he comes across as mostly hapless and naïve in spite of his awesome ace power. He never quite comes to terms with the fact that he’s only interested in helping a limited subsection of society, and that the jokers aren’t a part of it. He can’t abide their ugliness and misfortune, calling them “creatures” and purposefully avoiding the ghetto that is Jokertown.

That ambivalence surrounds other characters as well—for example, in The Godfather storyline that centers on Rosemary, Bagabond, and Jack. Rosemary is Michael Corleone; in WCI, she’d rejected the Mafia and her father (the Don) in preference for life as a social worker. Now, in Jokers Wild, she is the assistant district attorney, unhappily watching the Family lose its hold on the city amidst crime syndicate competition and escalating violence. The Mafia storyline has a twist, though. Whereas Michael Corleone, the unwilling son, took on his father’s mantle to preserve the Family, Rosemary herself cannot do so; she is a daughter, after all, and the Families are ingrained with a conservative Old World ethos. She becomes convinced that the Family will lose its prominence and thus bring instability to the city’s criminal underworld. At last she decides that her gender will no longer be an issue. By manipulating her friends and the Family itself, Rosemary manages to seize control of the Gambione syndicate during a restaurant massacre scene. Her story concludes at the end of the book when she symbolically takes her father’s place in the chair behind his desk.

Highs and Lows

There are many things to love in this book. Special honors go to the Bedtime Boys gang, who beat people with skateboards, and Popinjay’s early(ish) use of the insult “douchebag.” I also found myself partial to the meditation on images and art, expressed in the parade floats, wax figures, ice sculptures, and devotional iconography, but I’ll come back to that in a later post.

Although it’s only briefly explored, the impact of the Takisian virus on religion deserves mention: Wraith visits the amazing Our Lady of Perpetual Misery, reconsecrated to the Church of Jesus Christ, Joker. The post-virus theology represented in the Church, elaborated in the stained glass, Stations of the Cross, and sculpted doors, reveal a new (but eminently plausible) manifestation of Catholic suffering. The kindly Father Squid comes to the aid of Jokertown’s lost and tormented, following in the steps of recalcitrant Catholic social justice activists. I look forward to more Father Squid, and his flock, in later books.

For me, it’s a joy to spend time with several other characters, too. Although he’s not a POV in this book, Jay Ackroyd, the irascible gumshoe Popinjay, treks across town with Hiram, fighting the good fight and dropping smoking one-line zingers in his wake. If you’ve got a thing for rumpled but droll good guys with a cutting wit, Popinjay’s your man. Those on Croyd-watch will be sad to find that he barely makes an appearance, and the Turtle is only glimpsed from afar. Once more, alas, we spend far too much time in Tachyon’s pants, but Billy Ray shines as a slimy Fed brawler.

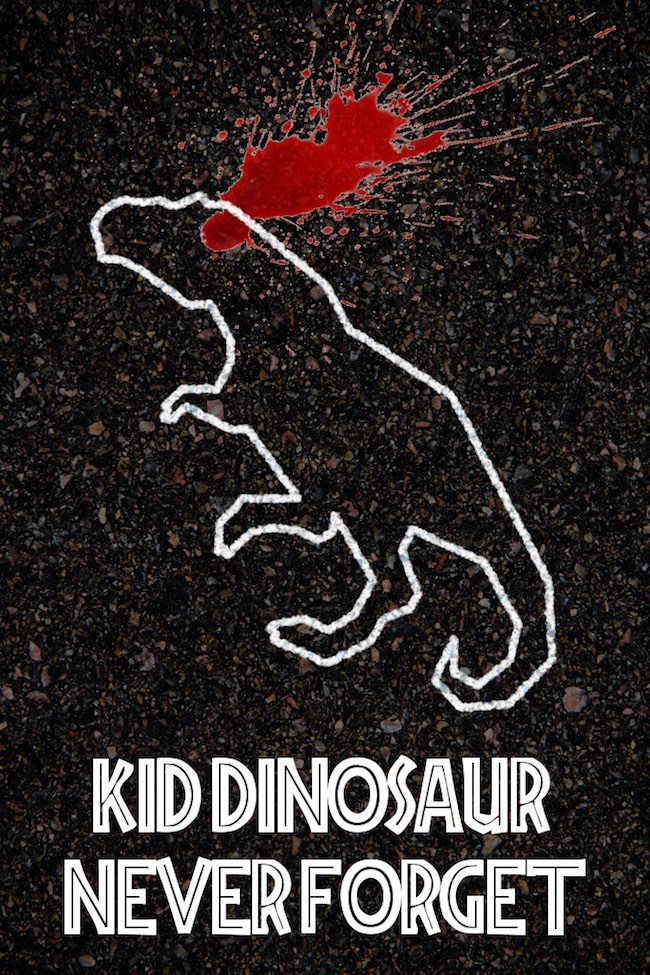

As you might guess, I rejoiced to see my fave, Kid Dinosaur, the star-struck juvie ace obsessed with heroes, who wants nothing more than to be one himself. We trail the kid over three books as he chases his heroes around NYC, getting underfoot but nonetheless managing to help. When not sneaking out of the house to help defeat the Masons at the Cloisters, he spends his time pranking Aces High, talking back to Tachyon, and stalking the Turtle. He’s idealistic and big-hearted and wants to save the world.

…But of course we all know what happens to the honorable and idealistic in books with George R.R. Martin’s name on the cover.

I remember the first time I read Kid Dinosaur’s death. I felt the way many people feel upon reaching a certain infamous event in A Song of Ice and Fire. I put the book down and stared at the wall. I flipped several pages back to make sure I’d read it right. My heart raced, my eyes welled, and I thought, “It can’t be true. It’s a trick.”

But it wasn’t a trick, and to this day I have NEVER forgiven the Wild Cards Consortium for what they did to Kid Dinosaur. AND I NEVER WILL.

Birth, Life, Death

Along with Demise, Roulette is the other major pawn of the Astronomer to be a major POV. She proves to be an unforeseen, fascinating character. She’s tasked with killing Tachyon but finds herself irresolute. Through her, we return to the subject of reproduction in the Wild Card universe, where carriers of the virus frequently give birth to babies with such severe defects that they can’t survive. It’s for this reason that the Turtle left the woman he loved, and why Wraith sees embalmed “Monstrous Joker Babies” in the Wild Card Dime Museum. Roulette, having lost her own baby (and been betrayed by her husband because of it), develops a murderous sex-related power.

Roulette is the wild card version of the vagina dentata, because she secretes deadly poison that transfers to her partner when she reaches orgasm. Sarah Miller notes that in ancient lit and folklore the vagina dentata’s “bite, rooted in the female sexual organ and aimed at the male sexual organ, transforms sex, which is an amalgam of pleasure and vulnerability, into a dangerous, bloody, deadly affair.”[1] With Roulette, the myth is pushed one step further because, rather than a dangerous toothy organ, instead it’s the female climax that kills her lover.

Jokers Wild continues to underscore the dichotomy between Fortunato and the Astronomer, already developed in WCII, as representatives of life and death. The distinction between them becomes explicit in the final showdown at the end of the book. In case we needed a reminder that the Astronomer represents evil, we’re given more snuff porn so that he can fuel his death magic-based bad-guy powers. As with Roulette, for The Astronomer, sex is death: “Death is the power. Pus and rot and corruption. Hatred and pain and war,” he crows. Fortunato reasons, “The Astronomer took his power from killing. The Astronomer was Death. Fortunato took his strength from sex, from life.” I’ve always thought the equation of sex with life was a bit overdone; after all, sex isn’t “life” or “creation” unless somebody makes a baby, and up to this point, Fortunato hasn’t done so. (Those who know what’s coming for Peregrine might argue otherwise, based on the Fortunato-Peregrine sex extravaganza).

The Astronomer, Roulette, and Demise act as a trio of death. Demise, of course, embodies his own end, which he shares with his victims via his gaze. Roulette is a parody of Fortunato. Rather than gaining power through sex, she kills with it; sex is her power, her power is death. Throughout her POV she repeatedly thinks of herself in those terms (“I should look like [Chrysalis], I’m Death”; “And in her secret place Death reveled.”)

Life wins in the end, of course, with the last few vignettes of the book emphasizing the concept of being fully alive in a variety of ways. It’s unambiguous for Fortunato, who becomes an amalgam of Asian philosophies in the final battle with the Astronomer. As a practitioner of Vajrayana (aka Tantric Buddhism), he’s attained his power through tantric sex (most recently with Peregrine, the now exhausted Yogini par excellence). Floating in lotus position he renounces his cares, finding non-attachment by “banishing fear. He clears his mind, finds the last thoughts that still snagged there–Caroline, Veronica, Peregrine–pulled them loose and let them flutter down toward the lights below.” At this point, he essentially reaches bodhi, enlightenment, and becomes Super Fortunato. We’re now moving into the realm of Theravada Buddhism.

Super Fortunato still isn’t enough to kill the Astronomer, sadly. Thus, he takes it up a notch and grabs for a wild card version of Parinirvana, which usually happens when a person who’s reached nirvana dies and their body (and reincarnation cycle) disintegrates; they become a non-essence—an absence-of-karma, a void. Fortunato reaches this point: “Nothing mattered; he became nothing, less than nothing, a vacuum.” Finally, having overcome all fear (“It was, after all, only death”), he disappears in a flash of light.

Of course, it turns out he doesn’t actually die (unless he instantly reincarnates, which woulda been kinda cool). Achieving victory over death, he’s still alive, deciding to give up all his connections to the world (family, pimping, etc.) to head off to Japan. Since he’s heading to a Zen Buddhist temple, I guess it’s bye-bye, Tantra, for now.

Beginnings and Endings

The 17-year-long saga of the Astronomer finally comes to a close, and the book winds up on a positive, even hopeful, note for most of the POV characters (even the non-heroic ones, like Demise). It also ends where it began, with Jetboy. The Wraith and Brennan storyline culminates at Jetboy’s Tomb, the building that marks the site where his plane crashed to earth forty years before. Inside, a replica of the JB-1 hangs from the ceiling as if at the Air and Space Museum; Wraith even ends up in the cockpit with Kien’s books. A huge statue of the doomed WWII kid pilot stands out front. There damn well better be a statue of Kid Dinosaur with him in the next book, honoring the juvie-ace at the spot he died, just like his pilot hero.

By the final chapters, we’ve come full circle. It’s Wild Card Day and, in an especially lovely moment, JETBOY LIVES! Sewer Jack looks up: “It was Jetboy’s plane. After 40 years, the JB-1 soared again above the Manhattan skyline. High-winged and trout-tailed, it was indisputably Jetboy’s pioneering craft. The red fuselage seemed to glow in the first rays of morning.”

He’s horrified, though, to see that the plane begins to break up, replicating the events of 1946. He realizes, though, that “it wasn’t the JB-1, not really. He watched bits of aircraft rip loose that were not aluminum or steel. They were fashioned of bright flowers and twisted paper napkins, two-by-fours and sheets of chicken wire. It was the plane from the Jetboy float, in yesterday’s parade. Debris began to fall slowly down toward the streets of Manhattan, just as it had four decades before.”

And hidden inside the float? A “steel shell, the unmistakable outline of a modified Volkswagen Beetle.” The watchers cheer in amazement as the Turtle flies off into the sunrise. The symbolism is clear. While the memory of Jetboy lives above the city, the nat ace war hero from the pre-virus world morphs into another flying ace, this time representing Jetboy’s successors, the new heroes of the wild card world.

[1] Miller, S. A. (2012). “Monstrous sexuality: Variations on the vagina dentate,” in Asa Simon Mittman and Peter Dendle (eds.),The Ashgate Research Companion to Monsters and the Monstrous (Ashgate Publishing), 311-28.

Katie Rask is an assistant professor of archaeology and classics at Duquesne University. She’s excavated in Greece and Italy for over 15 years.